This trilobite is not very big, nor does it have spines or an unusual rostrum. It is the plainest of trilobites, It achieved fame by dying in the right place -- in a layer of anoxic mud. Lacking oxygen, macroscopic scavengers like worms and crustaceans left it alone. Instead its innards were digested by anaerobic bacteria that excreted sulfide. The sulfide reacted with free iron in the water to produce FeS2 -- pyrite. So all the legs, antennae, and other soft parts got replaced with pyrite. The results are trilobites that show us in detail what living trilobites looked like, showing the parts that are usually missing.

There are five specimens here on four different rocks.

Specimen A is the only dorsal specimen, with a carapace about 2 cm long. If you went scuba diving during the Ordovician and looked down and saw a trilobite crawling along the sea bed, this is what it would look like. You can see antennae coming from beneath the carapace of the head and projecting forward. You can see legs projecting beyond the edges of the carapace. Note that the only preserved parts of the carapace are the pyritized portions -- the rest of the shell is missing, so there is only an internal mold of rock at the non-pyritized parts of the carapace. This is typical preservation for these trilobites.

Specimen B is the only dorso-lateral specimen, and is the smallest specimen, with a carapace 1 cm long. If you were shrunk down to the size of a trilobite and saw a trilobite marching by, this is what it would look like. This and specimen C (on the same rock) are the oldest specimens and the original gold color of the pyrite is now a duller, brassy color. But all the details are still preserved..

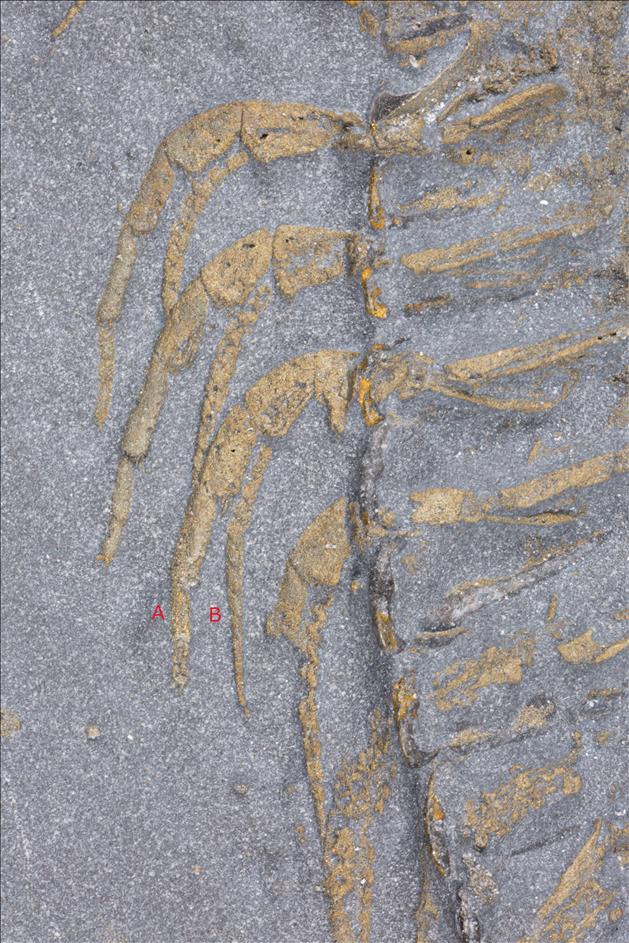

Specimen C is ventral and has a carapace just under 2 cm in length. The legs are particularly well preserved. Following the photograph of the full trilobite is a close up of the legs (on your left, the trilobite's right). Trilobites had jointed legs with an exoskeleton, a typical arthropod trait. If you had any doubts that trilobites are arthropods they should be dispelled by now. See how each leg starts as a unified entity but quickly splits into two parallel pieces, In the third leg down these pieces are labeled A and B. The more robust piece, labeled A, was a walking leg. The thinner piece, labeled B, had feathery fronds on it in life and acted as a gill. This arrangement of a walking leg below with a gill above it is called biramous. Trilobites had biramous legs, a primitive condition for arthropods. There are also two pairs of short legs under the head. Specimen E also shows the legs in the head well.

Specimen D is ventral and also has a 2 cm carapace. What is special about this specimen is that it has preserved ovaries. These are seen as the banded structure in the genal area of the head, on your right (the trilobite's left). The second photograph for this specimen shows a close up of the ovaries, and the the third photograph is identical to the second but shows the ovaries circled. This may seem an odd place to produce eggs, but that is just our chordate prejudice. Horseshoe crabs have a similar arrangement as trilobites.

If there are ovaries there should be eggs. This is where specimen E comes in, which is also in ventral position and has a carapace about 1.6 cm long. There are eggs in both the right and left genal areas of the trilobite. The eggs are small, about 120 - 200 microns long, which is about half the length of a Paramecium. Following a photograph of the entire trilobite are close ups of the left and right genal regions, and following those are the same two close ups, but with red arrows marking the eggs.

I hope I have convinced you that these are some of the most important trilobite fossils around. Not bad for a trilobite that with normal preservation would be primarily of interest to New York trilobite completeness collectors.